Page Archived

You have reached an archived page on TourTexas.com. Please use the search bar above to view other Texas content or reach out directly to the destination, attraction, accommodation or event shown on this page for up to date information.

History of the General Sam Houston Folk Festival

It was 1987, and the year should have been a good one for the Sam Houston Memorial Museum. The year before, Texas residents celebrated the state’s sesquicentennial anniversary in high fashion, and Sam Houston, of course, was prominently featured. More directly, 1987 marked the 50th Anniversary of the founding of the Sam Houston Memorial Museum. Fortune, it seemed, was favoring the Museum.Unfortunately, the Texas governor wasn’t. Armed with the line-item veto, Governor Bill Clements cut the Museum’s funding, leaving it, according to The Dallas Morning News, “doomed.”

Perhaps Houston would have appreciated the reversal of fortune. His favorite books, works by Homer and Virgil, addressed fate’s alternate cruelty and kindness, and he experienced such reversals in his own life — as when he had been nearly killed on the battlefield; or when he was nearly ruined by an ill-advised marriage and subsequent scandal; or yet again when he lost the Texas governor’s race in 1857; and finally, when he was forced from office in 1861 after refusing to endorse the Confederacy. But Houston was nothing if not resilient — a quality that apparently left a lasting impression on the citizens of Huntsville.

Showing their resilience, Huntsville citizens went to work. An “army” was mobilized, with officers, enlistees, and a mission to save the Museum — and, by extension, to protect the legacy of Sam Houston. “We’re taking the task at hand,” noted Bob Hardy in 1987, “and the museum is going to be open.”

Hardy was the “Adjutant General” in that army. Dean Lewis was the “Secretary of War;” Rip Byrd was “Public Affairs General;” Cecil Neely was the “Commissary General;” J. J. Head was “Inspector General;” and hundreds of local citizens marched as foot soldiers, and even paid a membership fee to do so, all in the effort to save the Museum. “Light is the task,” said Homer, “where many share the toil.”

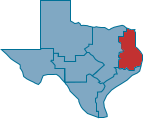

The collective effort was a success. There was a parade, a public relations drive, and (fatefully) the launch of the East Texas Folk Festival in 1988. “It was well produced that first year,” noted Scotty Cherryholmes, who participated in the inaugural effort. “The volunteer base was huge. Everyone from the mayor down to all the local organizations participated. We were concerned that we were going to lose that Museum, and it got people involved.”

The collective effort was a success. There was a parade, a public relations drive, and (fatefully) the launch of the East Texas Folk Festival in 1988. “It was well produced that first year,” noted Scotty Cherryholmes, who participated in the inaugural effort. “The volunteer base was huge. Everyone from the mayor down to all the local organizations participated. We were concerned that we were going to lose that Museum, and it got people involved.”

The funds from the Army membership and the Folk Festival brought in more than $50,000, which motivated the University to search for other sources of savings and income. The Folk Festival was born, and the Museum was open. Two years later, the Texas Legislature restored funding to the Museum, providing it with operational funds and a popular festival. “Fortune,” noted Virgil, “favors the bold.”

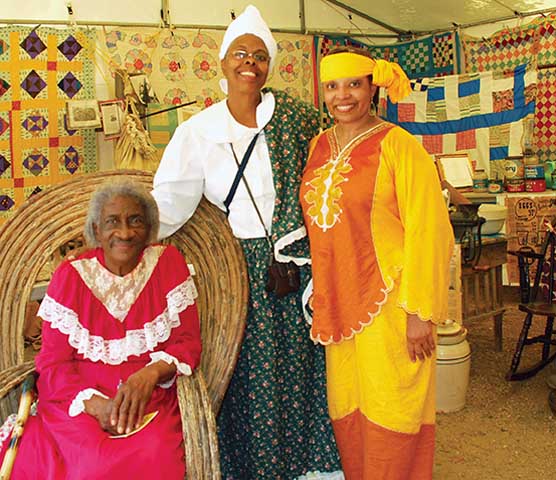

The spirit of the old “East Texas” Folk Festival remains, even as the event has evolved and grown. The name changed through common usage to the “General Sam Houston Folk Festival” in the early 1990s. In marketing terms, the change reinforced “the brand,” but it also emphasized the local community and its history, which is ineluctably tied to Sam Houston. “Houston’s significance,” observed Mac Woodward, the Director of the Sam Houston Memorial Museum, “as a military leader, a politician, a husband, and a father is what we want to highlight and celebrate.”

“The big change from the first Folk Festivals,” noted Cherryholmes, “was the decision to bring the event onto the grounds where Sam Houston lived. The grounds are a shrine, and they have been restored beautifully. It’s like a 19th century village.” These changes have enriched the event without changing its spirit, a spirit further reinforced by popular events performed annually.

Cart

Cart